Saw this tonight-

“

I'm not an economist. So last night, I asked someone who was to explain to me how the US Bond Market had just forced Trump to buckle. His initial reply was pretty ominous.

Here is the full explanation he gave me. It's his opinion, but I found it useful and got his permission to share it with you. He has a senior role with one of the major banks so has asked to remain anonymous.

Take from it what you will:

"The past 10-day saga begins with Trump’s goal to make America great again.

His dream appears to be a self-sufficient US—a hub of manufacturing, trade surpluses (exports > imports), low interest rates, and what he calls “American exceptionalism.”

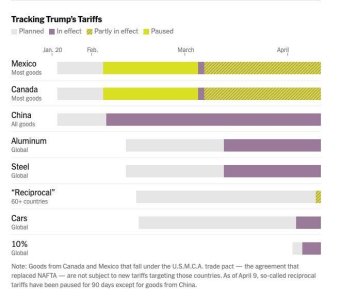

Trump used extreme tariffs of 25% on Mexico and Canada due to their apparent refusal to police their borders, particularly around drug importation.

It was rumoured that Trump wanted to begin his “Liberation Day” on 1 April. However, optically, it didn’t suit his “serious style” since it fell on April Fools’ Day. Therefore, Liberation Day was set for 2 April, with his plans kicking in a week later, on the 9th.

In the lead-up, many guesses and economist estimates were offered about worst-case scenarios for global trade and commerce. Some saw a flat 25% tariff as the worst case. Instead, we got what could be described as a “ChatGPT-style” plan: How do we tax a trade deficit?—a 10% floor with a scaled tariff based on the counterpart nation’s trade deficit. This is not a reciprocal tariff.

He had pledged high tariffs during his election campaign and brought Peter Navarro and Stephen Miran into the White House—both of whom endorse hyper-protectionism—alongside Stephen Bessent (former bond broker and hedge fund manager) as Treasury Secretary. Tariffs were set to go as high as 50%.

This extreme implementation shocked all markets. Global future economic growth rates were assumed to be dramatically lower due to higher costs, barriers to trade, and inflation—inevitable consequences of passing higher costs to consumers worldwide.

Forget the stock market—it’s a hoax. The real economy is driven by the cost of cash: interest rates.

Let’s take the RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia) as an example, though all central banks generally have a dual mandate: to maintain low inflation and support positive economic growth. Their main control lever is the official overnight cash rate.

Banks and firms must stay liquid. If a bank has excess deposits, it can lend them to the RBA or to another bank at the overnight cash rate.

Conversely, if it needs to borrow overnight cash, it can pledge collateral (such as government bonds) and borrow at that rate. Banks must also hold a proportion of High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) to ensure they can pledge collateral if needed. This is traditionally how central banks influence interest rates.

Over the past week, fears of global growth slowing to zero—or turning negative—due to tariffs (supply chain issues, extreme trade friction, geopolitical barriers between the world’s two biggest economies) have led to expectations that central banks will cut short-term rates to make borrowing cheaper for households, businesses, and governments. However, inflation is also expected to rise as a result.

This means: a short-term shock to growth, and long-term higher rates. That doesn’t fit anyone’s dual mandate.

The US bond market is the closest thing to God—assumed to be un-defaultable, safe debt.

But the US government runs a budget deficit. It spends more than it earns from taxes. Just this week, the US is borrowing around $100 billion. The 2025 budget deficit is expected to be $1.9 trillion, which must be funded through bond issuance. This is totally unsustainable.

The uncertainty in government policy has caused investors to demand higher interest rates. Why would I lend the US money for 10 years at 4% when in a year that could be 5%?

Think of HFT (high-frequency trading) in stocks. Now take that to the extreme in bonds. Traders and hedge funds arbitrage the difference between bond prices and derivatives like futures (meant to mimic the underlying asset). At futures expiry, the price of the future and the bond should match. Any difference before that is called the “basis,” and trading it is a “basis trade.” When the basis goes to zero at expiry, you profit.

But currently, confidence in US government policy is nonexistent. This has created a “sell everything” mentality, leading to massive dislocations in normally correlated asset markets. Even “safe” trades become volatile. No one wants to be the last out, and so the exits get crowded.

Currency markets amplify this. For example, Japanese investors who borrow at 1% in Japan to earn 4% in US bonds suddenly see the USD/JPY rate move 5% against them—wiping out gains. Why hold the trade?

Japan has been the largest holder of US bonds for a decade. China—now in the largest trade war in history with the US—is the second largest.

To summarise:

• The US is borrowing unsustainably, issuing bonds every month.

• It is imposing extreme tariffs on both friendly and non-friendly countries.

• (In my view) There is total mistrust in US government policy—protectionism in a global world.

• Stock markets are crashing. Over-leveraged bond trades are blowing up. Safe assets are being sold off.

• China may sell its US bond holdings in retaliation.

Who will continue to lend money to the US every week? Even the suggestion that some may not causes others to hesitate. This raises the cost of borrowing—interest rates go up.

Yesterday, bond markets were broken.

Sellers were dumping bonds at any price. People were asking if the US had ever cancelled a bond auction. The so-called safest asset in the world was no longer safe.

At a public event, CEA Chairman Steve Miran stated that to stop tariffs, one option was for other countries to “simply write cheques to the US Treasury”—effectively suggesting the US would renegotiate debt on its own terms, even with allies.

Simply put: The world is losing trust in the US as a safe place to lend money.

Bessent, the Treasury Secretary, is a former bond guy. He, like others, knows that lending and borrowing depends entirely on trust. If that trust is gone, lending dries up.

Trump, in my eyes, was forced to halt the tariffs to restore confidence in the US as a safe investment.

US interest payments on debt, in some months, are already higher than the tax revenues collected—at around 4.4% government rates. If confidence collapses and the US has to sell bonds at 6%, 7%, or higher, it becomes insolvent. It simply can’t afford to borrow.

Next, we’ll likely see:

• QE (central banks buying bonds, i.e., money creation—see: MMT)

• Zero interest rate policies

• Anything to lower short-term rates and pull long-term rates down

Trump’s policy, even in the short term, has broken the bond market—because everything hinges on the perception that borrowers will behave rationally."-

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com